ANDREA GEYER

2003

48 x 73 cm

Edition 4/5 (+2 A.P.)

Inv. Nr. 27

Born in 1971 in Freiburg, Germany

Lives and works in Freiburg, Germany & New York City, New York, USA

Andrea Geyer, who graduated from the Braunschweig Academy of Fine Arts in 1996 and attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program in 2000, investigates historical concepts such as national identity, gender and class. She uses both fiction and documentary strategies by blending narrative, historical data and theoretical elements in image and text-based works that form poignant social commentaries.

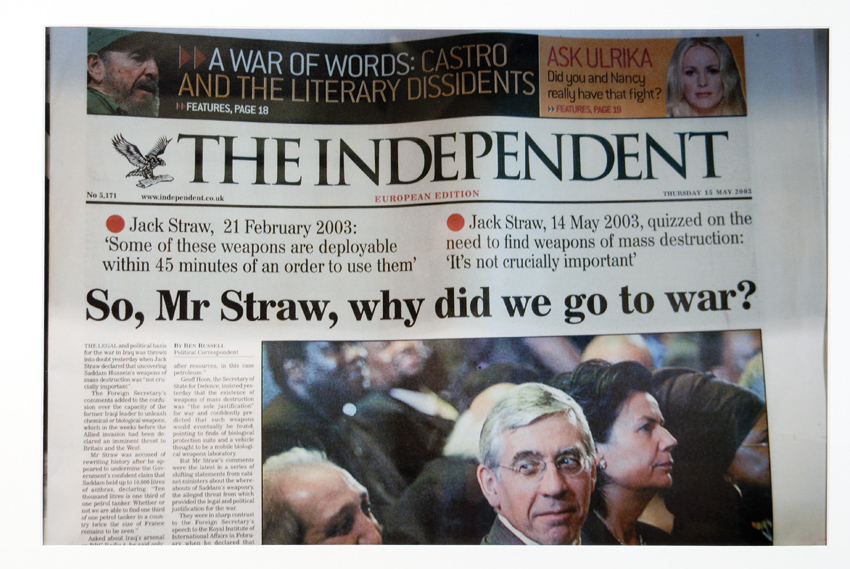

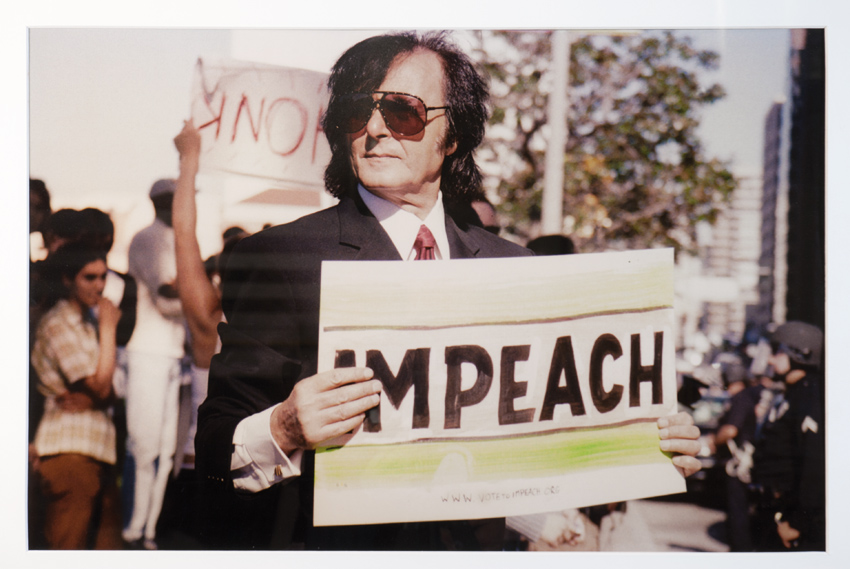

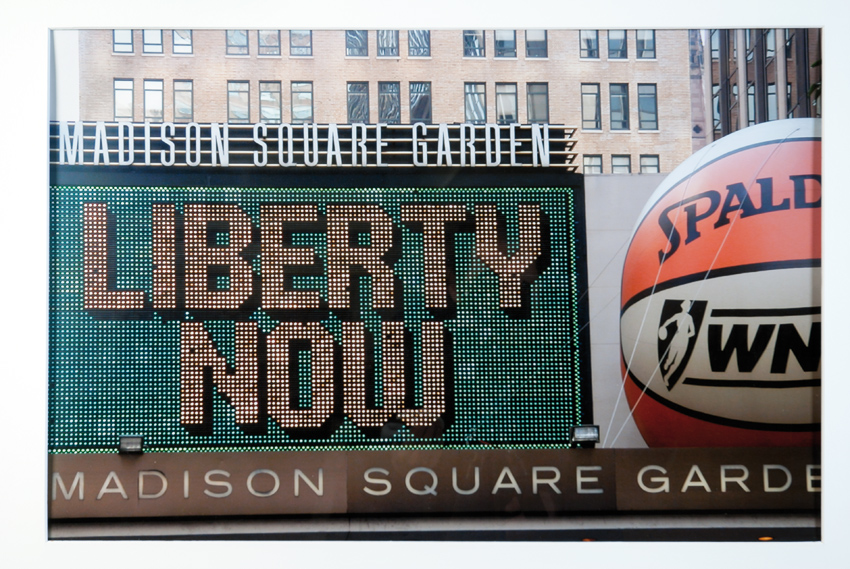

From September 2001 to August 2003, for her work Parallax, Geyer collected newspaper clippings and took photographs of public places, familiar monuments, courtrooms, museums and libraries of New York City. She had them edited into a fifty-minute silent slide show played through eight synchronized projectors in a loop. This work also exists as a series of printed photographs. Geyer’s work centres on the alienating condition of the metropolis but it is above all a chilling commentary on the corrosion of democracy in the U.S. after 9/11. After Allan Sekula or Chris Marker, she turns photographs into a documentary narrative revealing what obstructs our vision of reality.

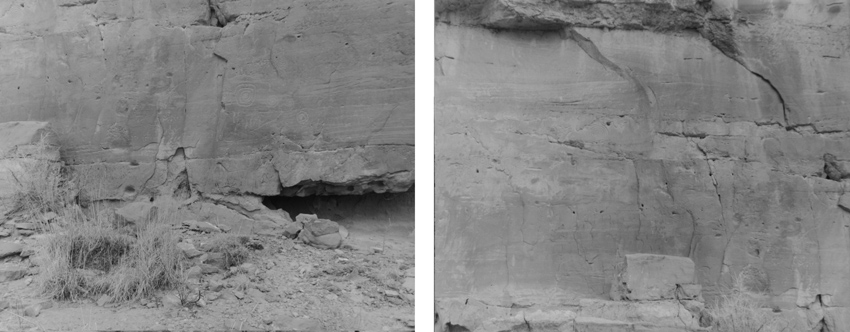

Spiral Lands. Chapter 1 is a series of photographs, which depict various natural environments of the American Southwest: vast horizons, desert scrub, and woodland, combined with panels of text describing the artist’s thoughts about this land based on Indian oral tradition and political discourse. Far from the mythic commonplaces of Hollywood Westerns, Geyer evokes the present-day paradoxes of this area: marked by a culture equally protected and exploited, fragile and enduring, since it is central in American imagination. By her use of layers of photographic and written documentation, Andrea Geyer invites the viewer to see this territory anew.

Audrey Munson, who was an artist’s model, was Andrea Geyer’s inspiration for a series of works. At her beginnings in the 1900s, Munson was soon the most sought after model by New York sculptors, who found that her strong features and penetrating beauty lent itself naturally to allegorical subjects. She appears in at least 15 sculptures around the city. Munson, who died in 1996, is a figure both omnipresent and totally forgotten. Her face held the attention of artists only for a few years. Dishonoured, she attempted suicide in 1922, which eventually led to her commitment to a state hospital for the insane in 1931. She lived in Ogdensburg, at the hospital, until her death, over sixty years later. Through this project, Geyer evokes the recurring patterns by which women are rendered invisible by patriarchal powers in a historical context. The series of pictures untitled Intaglio. Audrey Munson (2008) is an attempt to compile photographs taken by Geyer of the sculptures in New York City for which Munson posed. Geyer’s portraits capture the traces of the model’s real body, emerging from the classical manner of the sculptures. Silhouetted images, drawn from archive documents of suffragists and textile workers on strike are etched into the glass that covers each photograph. Geyer overlays dynamic historical events of the time in which these sculptures were created, returning their allegorical claims of civic unity and grandeur to their originally contested arenas.

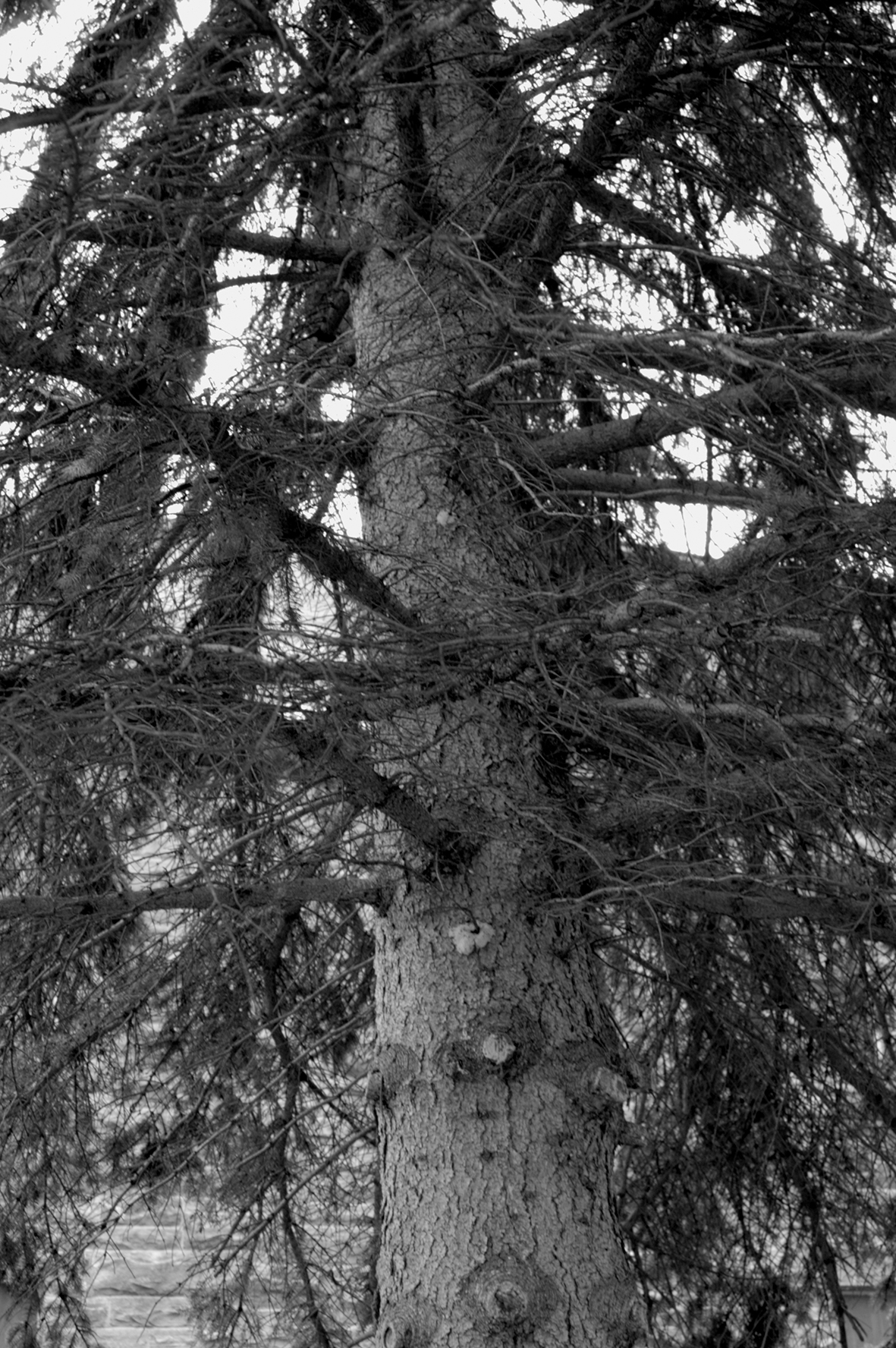

Companions of Exile (2008) consists of a series of photographs taken by Geyer on the site of the former St. Lawrence State Hospital for the Insane, where Audrey Munson spent most of her life. While architectural elements of hospital buildings appear in the distance, Geyer focuses on the tree trunks on the institution’s grounds, which continue to grow where human residents of the same area were once confined. Short texts written by Geyer are etched onto the glass. Each one is inspired by definitions of madness, insanity, and hysteria, especially concerning women condemned through their passion or rage to the institutions of late Victorian constraint.